Saudi Arabia, not the moral high ground

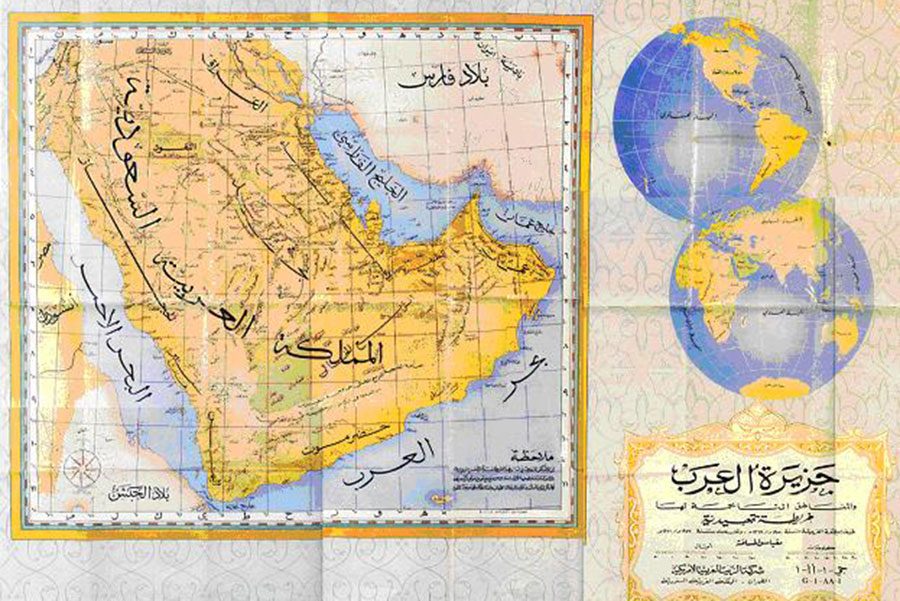

Caption: Since WWII, the United States has had strong diplomatic ties to Saudi Arabia.

October 31, 2018

The recent incident involving the death of a Saudi journalist has raised some serious questions about US foreign policy in the Middle East.

This month, Saudi Arabia has taken some serious heat both from Turkey, and (surprisingly) from Trump. The international community is responding to the Saudi government, finally admitting not only that Jamal Khashoggi, a dissident journalist, died while being held at the Saudi consulate in Turkey, but that the assassination was planned. This is only the lastest in a series of statements by the Saudis on the topic. The death of Khashoggi should be particularly important to the American people because Saudi Arabia is a close US ally. During this tumultuous time, many Americans are unsure how their president will respond. Some are calling for the President to cool its relationship with Saudi Arabia, and a number of American executives are pulling out of the Future Investment Initiative to be held in Riyadh. At first, Khashoggi’s death appears to be a change from the more liberal policies of Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, but a more extensive review of Saudi history reveals a consistently poor record.

The longstanding US relationship with Saudi Arabia dates back to World War II; American companies received permission to drill for oil in the country, and Franklin D. Roosevelt met with the Saudi King Abdulaziz. At the time, Saudi Arabia was already ruled by religious leaders who preached extreme interpretations of Sunni Islam. To this day, the country remains a theocracy, and Wahhabism, which preaches a very strict interpretation of the Qur’an, is only now losing some power.

Later, during the Cold War, Saudi Arabia was relatively well-aligned with American interests, helping to launch the Gulf War in 1991, and supporting western efforts to resist the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s. The US still has a strong strategic relationship with Saudi Arabia; politicians often praise its leaders as advocates for peace, and there are five American military bases in the country. Between 2008 and 2015 the Obama Administration sold close to $94 billion dollars in arms to the kingdom, and recently Trump has advocated for increasing that number.

Although arms has come up as an issue lately, the constant in the US-Saudi relationship has been oil. Saudi Arabia is an important member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which produces 40% of the world’s oil and represents 60% of the international oil market. In mid-1970s, when OPEC cut off western access to oil, the US economy was heavily impacted. In fact, the results of the shortage on the American auto industry can still be seen today in the dominance of more efficient Japanese brands. Even after this trade war, the US-Saudi alliance remained strong. Following the Iranian revolution of the late 1970s, Saudi Arabia became the sole stabilizing Arab power allied with the US, and following presidents viewed the Saudis as something of a geopolitical necessity.

However, the relationship has long been a compromise. The Saudi human rights record is shaky to say the least; the Kingdom restricts free speech, lacks due process, violates women’s rights, exploits immigrants, and otherwise acts in ways that do not align with democratic values. Saudi human rights abuses are not exclusively domestic, either. At least 6,500 civilians have been killed in bombings by Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates in pro-government efforts in the Yemeni Civil War; the UN found that “coalition air strikes have caused most direct civilian casualties” and action in the country “may amount to war crimes.” Even more horrifying, many of the strikes that have killed civilians have been carried out with American bombs.

The Saudi government does not actively support terrorism, and has been a US ally in counterterrorism efforts. However, Saudi non state actors have been tied to funding for terrorist groups, and of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers, 15 were Saudi. None of these implicate the government directly, but it is indisputable that the Kingdom has become an exporter of Islamic fundamentalism. Wahhabism emanates from the Kingdom. Wahhabi universities, individuals, and churches spread their books, preaching styles, and funding throughout the world.

Still, it’s important to note that Saudi Arabia is not the only US-aligned perpetrator of human rights abuses in the Middle East. The Turkish government, which has so adamantly condemned Saudi action, has also been found guilty in the past of human rights violations. Under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, democratic institutions have been undermined, freedom of speech violated, and political opponents have been jailed and, in some cases, tortured. These actions make it clear that the Turkish position towards Khashoggi is not so much about protecting human rights as it is hurting a geopolitical adversary, Saudi Arabia.

In fact, the US situation with Saudi Arabia is analogous to the EU-Turkey relationship. The EU and Turkey have an agreement in which the latter halts the flow of migrants, many of them from Syria, and in exchange the EU provides financial support for Turkish relief programs and accepts some vetted refugees. This is all part of the Turkish goal of closer cooperation with the EU and possibly eventual membership. Just as the US is aligning itself with a morally-dubious state, so is the EU. Policies such as these are common in developed countries relationship with the developing world; concessions are often made in terms of democracy and human rights in order to gain stability and influence.

Hopefully, the Khashoggi incident will bring about a reckoning. Saudi Arabia may have been a necessary ally during the Cold War, but the fight against communism is largely over, and as US energy reserves at home are now more productive, the compromise is no longer unavoidable. It’s time for a change, not only in the US-Saudi relationship, but in American foreign policy toward anti-democratic states.

The American record on supporting dictators is imperfect to say the least. In the last century, the land of liberty has actively supported dictators in Vietnam, Indonesia, Bahrain, Guatemala, Chile, Romania, Uzbekistan, and a plethora of other countries. Many of these states were democracies before intervention. For a nation that is supposed to be a “bastion of democracy,” and the “leader of the free world,” the US has supported multitudes of corrupt, dictatorial, and oppressive regimes. American foreign policy is often justified as “spreading and protecting democracy,” but in reality, many uses of military and economic force have been to the opposite effect.

How can the United States use one hand to endorse the freedom and individual rights of capitalism and democracy, and then use the other to shield despots from harm? Do the people of foreign countries have any less of a right to self-determination than Americans? The time has come for comprehensive reform of US relations to its fellow people, so that rather than manipulating the governments of other nations, it actively advocates for liberty and democracy. The support of autocratic regimes may be an American tradition, but it is one that most certainly ought to die.