Mohawk Tannery: A reminder of Nashua’s industrialized past

Commercial fencing surround the grounds of the proposed Superfund site where the former tannery remained in operation from 1924 to 1984. Throughout the lifetime of the plant, chemicals involved in the leather-tanning process were discharged into on-site lagoons.

March 26, 2019

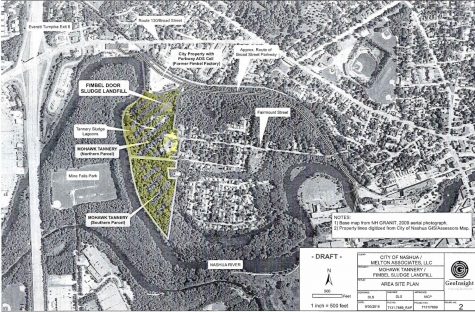

On approximately thirty acres on Fairmount Street in Nashua lays the remnants of the once thriving Granite State Leather company, commonly referred to as Mohawk Tannery, which remained in operation for nearly sixty years. With the site now nearing three-decades since its closure, the graffiti-vandalized foundation is now the only way to establish the location of the plant’s original structure.

Thwarted by chain linked fence and evergreen-colored privacy slabs, the site leaves the public questioning the progress of the project’s current state. The practices completed throughout the lifetime of the company have left an area plagued with contaminants and a public at risk of adverse health effects. Adjacent chemical sludge lagoons located in the nearby Nashua River’s one-hundred year floodplain provide an observer with the sheer scale of the problematic area.

After the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed the project to its National Priorities List in 2000, asbestos construction materials and tanning drums containing hazardous waste were removed, and the area was fenced off to protect the surrounding public. Chemicals from the tanning process remain in seven large “lagoons” throughout the property that contain chromium, mercury, lead, arsenic, silver, cadmium, pentachlorophenol, methylene chloride, chlorobenzene, and trichloroethylene; nine of which are labeled “likely, potentially and definite cancer-causing compounds” by the American Cancer Society and EPA. Extensive testing of the site’s soil from 1989 to 2018 concluded that PCBs, asbestos and the chemicals earlier mentioned are present throughout the property, whilst the quality of groundwater continues to be questioned despite numerous measurements of water samples. “Mohawk” is currently placed on the Superfund sites targeted for immediate, intense action, but has remained without National Priority status and funding.

As per the City of Nashua’s decision, the planned cleanup of the site was halted due to the belief that the land is capable of development, meaning an investor could potentially remediate the site via private funds. Since the land is without an accountable owner, local government, in partnership with federal agencies, is responsible to foot the expensive bill. In a July 2018 EPA site update, rehabilitation options were estimated to cost taxpayers anywhere from 8 to 32.6 million dollars. Inflated estimates have led many members of the public looking toward private developers for remediation of the former tannery’s grounds. A petition signed by 120 individuals, sponsored by the North-East-West Nashua Civic Association, calls on the EPA to “revitalize this hazardous site by cleaning up all contaminated and potentially contaminated areas at the Mohawk Tannery Superfund site and its surroundings.”

As New Hampshire Public Radio reported in Nov. 2018, a viable buyer of the Mohawk Tannery property is actively seeking to redevelop the brownfield land for housing, with a plan of erecting some hundred multi-story units. The prepared purchaser, Bernard Plante, plans to encapsulate the affected area after condensing the contents of all satellite pools into the two largest.

The future rehabilitation of the site remains in question while negotiations continue. The EPA and NH Department of Environment Services’ Project Managers did not reply to our request for comment on the current state or planned remediation of the site.