Grades are a central part of a student’s educational experience. Through the CavChron’s investigation into Grading Structures & Practices, we hope to shed light on Grading Philosophies, Rapid Grade Access, Midterms & Finals and Class Rank.

Grading philosophies and policies have always been a common topic of discussion in education. There are countless questions teachers have to consider when determining how they grade: “What meaning should each ‘grade’ carry? What are the criteria you use to assess?

How should class grades be distributed?” and the list goes on. It is important for teachers to both follow standard policies for grading, but also to develop their philosophy that best suits their teaching style and curriculum.

According to the Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, teachers should follow 12 basic principles when it comes to grading. In summary, the list encourages teachers to use grades as a benchmark for learning, while still prioritizing learning in their classes and collaborating with their students to create the best educational environment. These basic philosophies are very standard in schools across the country and can be seen in almost every classroom. “We may each have individual ideas and philosophies, but we think students taking the same course should be managed and graded in the same way,” said Stacey Plummer, who teaches classes ranging from Geometry to AP Calculus at HBHS. Consistency is important to some degree and makes the grading process easier for both students and teachers.

Although common grading practices are important, there are also personal philosophies that are unique to each teacher. While some classes, such as math and science, often require more objective grading systems, teachers still have to make decisions when it comes to their grading philosophies for each class. For example, teachers often differ in their opinion of whether or not homework should be graded, furthermore if it should be graded for completion or accuracy.

These policies often vary from course to course, depending on difficulty. “Our whole set of grading practices and philosophies and policies are all centered around understanding that there are major differences between a fourteen year old freshman and an eighteen year old graduate,” said Stacey Plummer. Evidently, one of the major factors that goes into grading decisions is the level of the class. “The goal of an AP class is for me to help kids learn and master the skills that they need to do well on the AP exams… With world studies (a grade level history class) there’s a lot more flexibility; I’m essentially looking at the same skills but I give a little bit more leeway,” added Christina Ellis, a World Studies and AP World History teacher at HBHS. Teachers often aim to make the difficulty, and therefore importance of grading, progress over time as students begin to take more advanced classes that more closely model college classes.

Another area where opinions may differ in the educational world is whether or not partial credit should be given on tests. This also largely depends on the difficulty and subject matter of the class. “I try to give partial credit for understanding and look for understanding,” said Steven Crooks, an AP Physics 1 and 2 teacher at HBHS. This allows students to receive credit for their understanding of topics, even if they did not get the right answer to a particular question. Other teachers may decide not to give partial credit on their assessments, often in an effort to prepare their students for college grading systems that typically don’t offer this. Both policies can be very effective and suit different curriculums; it is ultimately the teacher’s decision to determine their own set of policies that include or exclude partial credit.

Another area where different teachers or departments may differ in opinion is using weighted categories for grading. Grading in a class can be split into different categories, such as homework and tests, that will hold a certain percentage of the overall grade. “We do weight categories but a little more broadly. What you would consider to be homework or daily practice in some classes would be ten to twenty percent of your grade and the rest of your grade is made up of… the assessment category,” said Stacey Plummer. The math department at HB has a somewhat standard policy for grading categories, but it certainly differs from department to department.

“We do summative and formative grades. Summative grades are your heavy grades: your projects, quizzes, tests. Those are meant to demonstrate learning after it has been done,”

while “formative grades are the assignments that are meant to teach you something and the learning that goes along with it,” said Christina Ellis. The classes she teaches are best suited by a more even distribution of grade percentage between classwork and assessments. Language arts classes have a system like Ms. Ellis’, while STEM based courses usually weigh assessments more heavily. Again, the level and difficulty of the class also have a big influence on the teachers’ decision to grade certain categories more heavily.

Countless hours could be spent discussing grading policies and philosophies, but every teachers’ philosophy should come down to one essential question: what do you believe the primary purpose of grading is, especially in the classes you teach? The answer to this question can help teachers shape their policies and guide them to adapt to the needs of their class when it comes to grading.

“From the school’s perspective it’s a way of saying ‘Is this working at all?’’ but, “grades are [also] an incentive to learn especially when there is a test or a quiz coming up,” said Steven Crooks.

“It’s measuring a student’s aptitude within the skills that they are learning, and it’s also about demonstrating how they are improving and how they are getting better at skills over time,” added Christina Ellis.

“The primary purpose of assessment is for both you, as the student, and I, as the teacher, to be able to give each other feedback,” concluded Stacey Plummer.

Grading policies and differing philosophies can be controversial, but the discussion should always come back to what the primary purpose of grading should be when it comes to benefitting the student.

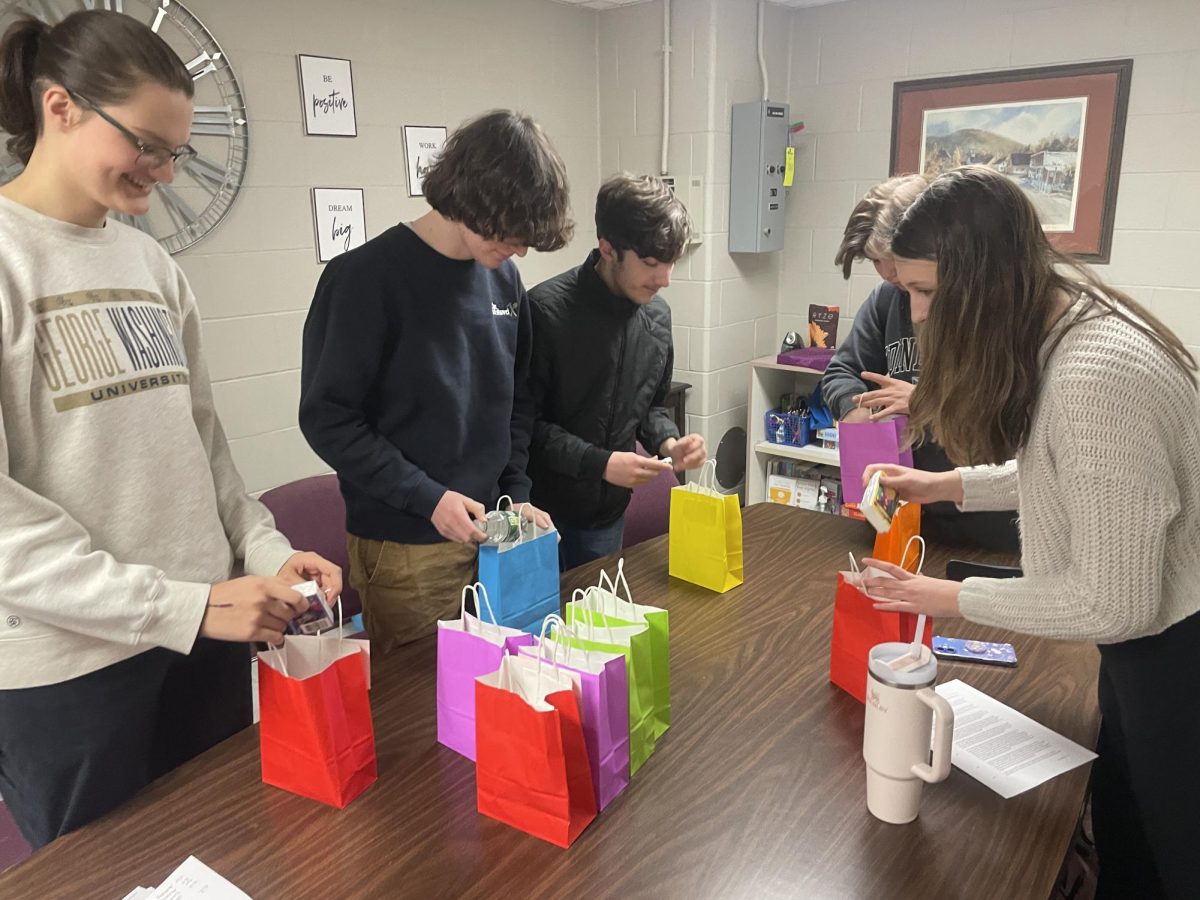

![Steven Crooks grades a lab from his AP Physics 1 class. He is a new teacher, but already helping his students succeed with his grading philosophies and policies. “I want to see the thought process [in their work],” said Crooks.](https://cavchronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Grading-Philosophies.jpg)